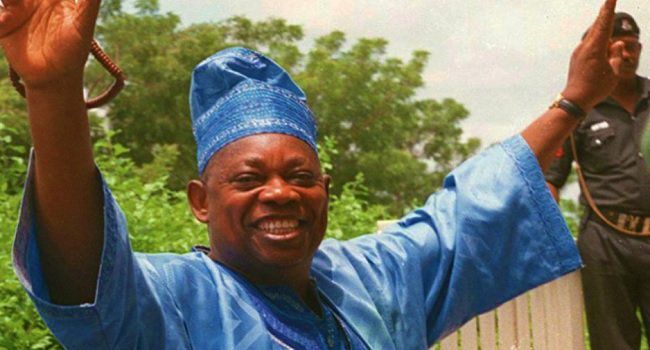

The historic Epetedo declaration represented a significant shift in late Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (MKO) Abiola’s struggle to claim his mandate following the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election.

The bold move solidified his reputation as a man of valour with firm conviction who refused to betray his principles even in the face of great danger.

Victory Denied: June 12, 1993 Annulment

Running under the Social Democratic Party (SDP), Abiola had swept the majority of the votes in the election, winning 20 out of 30 states against his only challenger, Bashir Tofa of the National Republican Convention (NRC).

However, then-military Head of State General Ibrahim Badamosi Babangida (IBB) threw a monkey wrench into the process, arbitrarily halting the results announcement and upending the hopes of millions of Nigerians.

Subsequently, Babangida annulled the election, which is considered the freest and fairest in Nigeria’s history. That annulment caused a political crisis and triggered national outrage that forced him out of office and paved the way for General Sani Abacha to seize power from the interim government of Chief Ernest Shonekan later that year.

With the coming of Abacha came an intense agitation among the masses, with the perceived injustice fueling protests against the government and resulting in violence that claimed lives.

Nearly a year after the election and shortly after returning from a trip to win the international community’s support for his mandate, Abiola made a last-ditch attempt to claim his mandate.

On June 11, 1994, he declared himself the lawful democratic president of Nigeria in the Epetedo area of Lagos, mainly populated by Yoruba Lagos Indigenes.

Excerpts from Abiola’s Epetedo declaration read:

“To be precise, you gave me 58.4% of the popular vote and a majority in 20 out of 30 states plus the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja. Not only that, you also enabled me to fulfill the constitutional requirement that the winner should obtain one-third of the votes in two-thirds of the states.

“I am sure that when you cast an eye on the moribund state of Nigeria today, you ask yourselves, ‘What have we done to deserve this, when we have a president-elect who can lead a government that can change things for the better? Our patience has come to an end.’

“As of now, from this moment, a new Government of National Unity is in power throughout the length and breadth of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, led by me, Bashorun M.K.O. Abiola, as President and Commander-in-Chief.

“The National Assembly is hereby reconvened. All dismissed governors are reinstated. The State Assemblies are reconstituted, as are all local government councils.

“I urge them to adopt a bipartisan approach to all the issues that come before them.”

Abacha arrested and detained Abiola for treason

The repercussions of Abiola’s self-declaration as President were immediate and brutal. In response, the military regime declared him wanted. Abacha dispatched 200 police vehicles to effect his arrest.

The philanthropist was swiftly apprehended and detained on charges of treason against the Nigerian state. This arrest marked the beginning of a protracted and controversial incarceration.

Abacha resolutely refused to free the billionaire despite mounting international and domestic pressure for his release, including appeals from numerous human rights organisations, diplomatic bodies, and influential figures.

Abiola was held in custody for four long years with his fate hanging precariously. This sparked heightened political instability, social unrest, and condemnation from the international community, but the regime dug its heels in.

Abiola’s torrid time in prison and global pressure for his release

Abiola’s harrowing four-year detention was a period characterised by extreme isolation. Mainly condemned to solitary confinement, his only companions were a Bible, the Qur’an, and a rotating detail of 14 guards who maintained close monitoring to ensure his unwavering imprisonment.

This persistent detention attracted international attention, as prominent figures and organisations rallied for his release. Pope John Paul II and Archbishop Desmond Tutu were among numerous human rights activists from across the globe who exerted persistent diplomatic pressure on the Abacha regime.

The collective advocacy for Abiola’s freedom underscored the global concern surrounding his unjust detention, forcing the military government to offer him a conditional release. However, the offer was a poisoned chalice.

Abacha wanted Abiola to trade his mandate for his freedom. He demanded that he publicly renounce the electoral mandate given to him in the 1993 election, but the billionaire unequivocally declined.

Despite the substantial financial incentives offered by the military regime, including compensation and the reimbursement of his considerable election expenses, Abiola stuck to his guns and chose to fight on. His unwavering commitment to the mandate became a defining aspect of his imprisonment.

However, the ensuing episodes hinted at the waning interest of the international community. In 1998, a deeply troubling episode arose when the then-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan and Emeka Anyaoku, then the Secretary-General of the Commonwealth of Nations, informed the international community that Abiola had purportedly agreed to renounce his mandate.

The claim emerged after the duo met with the philanthropist and conveyed that the international community would not recognise an election that had occurred five years prior.

The report contradicted Abiola’s steadfast refusal to concede, leaving him profoundly disturbed. The episode raised questions about the nature of the discussions that had taken place during the meeting and created a sense of betrayal and confusion, further complicating Abiola’s already dire situation.

The disparity between Abiola’s persistent stance and Annan and Anyaoku’s claim cast a shadow over the international efforts to secure his release and fueled speculations about potential miscommunications or misrepresentations.

MKO remained in limbo as the situation persisted until the sudden and unexplained death of General Abacha on June 8, 1998.

Abacha’s demise, whose circumstances remain a subject of speculation and debate, offered a glimmer of hope for Abiola’s liberation. This brought a shift in the political landscape, and the path to his freedom appeared finally open.

However, a tragic turn of events occurred when Abiola himself died under similarly mysterious circumstances just a month later on July 7, 1998.

The circumstances surrounding his death also fueled controversy and suspicion, leading to various theories and investigations.